Catechism : Life in the Spirit

29. Conscience (n. 1776-1802)

In this chapter we reflect on the role of conscience in the moral life (see Catechism n. 1776-1802).

Truth

We begin our reflections by focusing on the importance of being in touch with what is real, with the way things are, as distinct from the way we might like things to be; in other words, the importance of truth. The Second Vatican Council, in its Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis Humanae (1965), has this to say:

‘All are bound to seek the truth, to embrace it, and to hold on to it as they come to know it. The sacred Council proclaims that these obligations bind the human conscience.’

Nothing is gained by living in a world of make-believe. The Council goes on to make an important point:

‘Truth can impose itself on the human mind only in virtue of itself as truth, which wins over the mind with gentleness and power’ (n. 1).

There is a certain pleasure, a sense of well-being, which we experience when we are in touch with the truth. We sense this imperfectly, and so we long for a deeper consistency and a more profound integration, which we can have only when we are perfectly in harmony with reality. This involves us in a constant journey of discovery, and demands decisions of us – decisions based, not on habit or unreflecting instinct, but on insight enlightened by faith. Experience continues to teach us the wisdom in Jesus’ words:

‘The truth will set you free’(John 8:32).

The cult of spontaneity can leave us trapped within the confines of merely bodily gratification, or gratification of the ego, ignoring the more profound and personal longings of the human spirit.

In his encyclical The Splendour of Truth, Pope John-Paul II writes:

‘The maturity and responsibility of the judgments of conscience are measured by an insistent search for truth, and by allowing oneself to be guided in one’s actions by the truth’(n. 61).

‘Conscience expresses itself in acts of judgment which reflect the truth about the good, and not in arbitrary decisions. The maturity and responsibility of these judgments – and, when all is said and done, of the individual who is their subject – are not measured by the liberation of the conscience from objective truth, in favour of an alleged autonomy in personal decisions, but, on the contrary, by an insistent search for truth and by allowing oneself to be guided by that truth in one’s actions’(n. 85).

Criteria for making truthful decisions

Let us look briefly at criteria we might use for determining what decisions are in accordance with the truth (and so morally right). One criterion is obedience to the law. However it is inadequate when it comes to discerning truth, for, just as an action that is permitted by law may still be morally wrong, so an action that is forbidden by law may still be morally right. There is more to acting morally than simply following a law.

We must also be careful when we claim to be following our own conscience. As we will note shortly, ‘following one’s own conscience’ can involve much more that might appear at first glance. It is certainly much deeper than acting on one’s present opinion or preference. We have a basic obligation to seek the truth. This involves us in a lifelong journey of forming and informing our judgments. We can be ill-informed. Our judgment can be quite wrong. The fact that I judge something to be true does not make it true. Acting on our own judgment can cause a lot of harm to others and to ourselves. As Pope John-Paul II says in his encyclical The Splendour of Truth:

‘One’s moral judgment is not true merely by the fact that it has its origin in the conscience. To hold this would mean that the inescapable claims of truth disappear, yielding their place to a criterion of sincerity, authenticity and being at peace within oneself’(n. 31).

Sincerity, authenticity and being at peace within oneself are important, but they are not adequate as criteria for truth.

Another criterion we might use in making decisions is that of doing what everyone does. To accept this as a criterion for truth and morality would be to ignore the problem of sin and bias.

Five Essential Imperatives

Truth is not something that we decide and impose on reality. Truth is something we discover, when the judgments we make about reality are consistent with the way things really are. In some easy areas, truth is not difficult to discover. In most matters, the discovery is an unfolding process. Truth is something we approach rather than possess. Bernard Lonergan, a Canadian Jesuit, speaks of five imperatives that we simply must follow if we are to have any hope of discovering and acting on truth. The first and most basic imperative is that we must be attentive to reality and to our response to it. Secondly, we must behave in an intelligent manner, by living a reflective life and searching for meaning in our experiences, not satisfied to jump from one experience to the next. Being intelligent will, in turn, make us more attentive. Thirdly, we are to be reasonable. That is to say, we must check any insights we may think we have, so that we will come to know how things really are, as distinct from how they seem to us to be. After all we want to know what is real. A moral life is not something fanciful or escapist. Fourthly, we are to be responsible. We are to respond in a creative and personal way to what we discover to be real. If we neglect to behave responsibly, we can be sure that we will be tricking ourselves into avoiding to see and know what could prove awkward. As the adage goes: ‘None so blind as those who refuse to see.’

Finally, we are to ‘believe’, that is to say, be open to give and receive love. Being in love (be-lieving) is the great teacher. Saint Augustine writes:

‘Do not seek to understand so that you may believe; believe so that you may understand.’

If we do not follow this advice we run the risk of confining our openness to reality within the limits of our logic and intelligence. Believing (I am assuming that we do this in a reasonable way) can open us to the wonder of reality that would otherwise remain beyond our ken, Paul seems to be saying this when he writes:

‘This is my prayer, that your love may overflow more and more with knowledge and full insight to help you to determine what is best’(Philippians 1:9-10).

It its Decree on Priestly Formation, Optatam Totius (1965), the Vatican Council has this to say:

‘Moral theology should show the nobility of the Christian vocation of the faithful, and their obligation to bring forth fruit in love for the life of the world’(n. 16),

Helped by Others

In our search for truth we are influenced by others who can help or hinder us, both as regards our internal formation (which gives rise to the questions we ask) and in our external information (which affects the answers we discover). W. Cosgrave in an article entitled “What is Conscience?” in Doctrine and Life 1984, page 554, writes:

‘A person never comes to a particular moral choice or situation as a moral blank or in a morally neutral state. He is always already conditioned and formed in basic ways for both good and ill, and this will inevitably and significantly show itself in the concrete moral decisions he makes.’

An especially significant role in forming conscience is played by the Spirit of Jesus working through those who are graced with teaching authority in the Church. Alluding to Paul’s words, Pope John-Paul II writes in his encyclical The Splendour of Truth:

‘The Church puts itself always and only at the service of conscience, helping it to avoid being tossed to and fro by every wind of doctrine proposed by human deceit and helping it not to swerve from the truth about the good of the human person, but rather to attain the truth with certainty and abide in it’(n. 64).

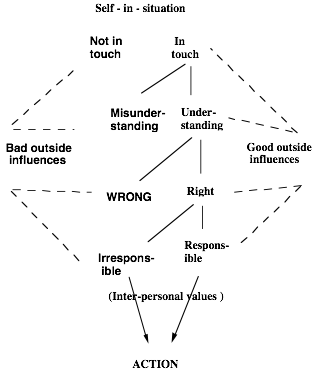

The following diagram aims to set out the effects of good and bad influences on our behaviour:

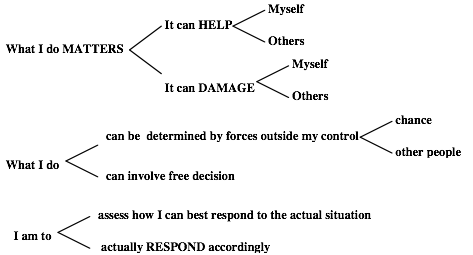

Another diagram may help illustrate certain processes involved in making decisions, and what we are to do to act morally.

Seeking help to make a good decision

When people seek help in making a conscientious decision, sometimes they are saying little more than ‘I am not sure what to do.’ We can help by exploring the matter with them and helping them find a basis on which they can make a decision. At other times they are wanting to know what the Church teaches. We can inform them on this, being careful to explain the source and level of importance of the teaching. Sometimes they know what the Church teaches but are looking for support in acting contrary to the teaching. They may be seeking permission, which, of course, cannot be given. The taking of a decision is their right and their responsibility. They may want us to make them feel better about the decision they are determined to take. We can’t do this either. Dealing with their feelings is something no one can do for them. They may be asking how God will ‘feel’ about what they are doing. We need to speak about God as a God of love who will continue to love them whatever they do. They cut themselves off from welcoming this love only if they knowingly and willingly do what they know is against God’s will in a matter of grave importance. Their responsibility is to do all they can to do what seems right for them here and now in the real circumstances of their life.

If, however, they are really saying: ‘I have thought and prayed about this, and researched it carefully.I know that the Church says X, and why, and I believe it is true, but in the circumstances I believe I have no real alternative but to do Y. I wish I could do X, and I will as soon as I can, but at the moment I truly believe that Y is the best I can do. Where do I stand before God?’ Regardless of the conclusion they have reached, this person has done all that the Church asks them to do in making a decision in conscience, and the Church teaches that this person has a duty to follow that decision.

The relationship between the Magisterium and conscience is clarified by the ‘Washington Document’, issued by the Sacred Congregation for the Clergy on the 26th April 1971 in response to the difficulties people were having in accepting the teaching of Pope Paul VI on the regulation of conception. It reads:

‘Conscience is the practical judgment or dictate of reason by which one judges what here and now is to be done as being good, or to be avoided as evil. In the light of the above, the role of conscience is that of a practical dictate, not a teacher of doctrine. Conscience is not a law unto itself and in forming one’s conscience one must be guided by objective moral norms, including authentic Church teaching. Particular circumstances surrounding an objectively evil act, while they cannot make it objectively virtuous, can make it inculpable, diminished in guilt, or subjectively defensible. In the final analysis, conscience is inviolable and no one is forced to act in a manner contrary to his or her conscience, as the moral teaching of the Church attests.’

At about the same time, an important clarification was given by the Canadian Bishops:

‘In matters which have not been defined ex cathedra, i.e. infallibly, the believer has the obligation to give full priority to the teaching of the church in favour of a given position, to pray for the light of the Spirit, to refer to Scripture and tradition and to maintain a dialogue with the whole church, which he can do only through the source of unity which is the collectivity of the bishops. The reality itself, for example, sex, marriage, economics, politics, war, must be studied in detail. In this study the believer should make an effort to become aware of his own inevitable presuppositions as well as his cultural background, which leads him to act or react against any given position. If this ultimate practical judgment to do this or avoid that does not take into full account the teaching of the church, an account based not only on reason but on the faith dimension, he is deceiving himself in pretending that he is acting as a true Catholic must. For a Catholic “to follow one’s conscience” is not, then, simply to act as his unguided reason dictates. “To follow one’s conscience” and to remain a Catholic, one must take into account first and foremost the teaching of the magisterium. “In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent of soul. This religious submission of will and of mind must be shown in a special way to the authentic teaching authority of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra”(Vatican II LG n.25). And this must be carefully distinguished from the teaching of individual theologians or individual priests, however intelligent or persuasive.'

In September 1974, and from within the same context, the Australian bishops wrote:

‘It is not impossible that an individual may fully accept the teaching authority of the Pope in general, may be aware of his teaching in this matter, and yet reach a position after honest study and prayer that is at variance with the papal teaching. Such a person could be without blame; he would certainly not have cut himself off from the Church; and in acting in accordance with his conscience, he could be without subjective fault.’

Revelation and the Magisterium are at the service of conscience. The Catechism states:

‘In the formation of conscience the Word of God is the light for our path (Psalm 119:105); we must assimilate it in faith and in prayer and put it into practice. We must also examine our conscience before the Lord’s Cross. We are assisted by the gifts of the Holy Spirit, aided by the witness or advice of others and guided by the authoritative teaching of the Church’(n. 1785).

Conscience and the inner inspiration of the Holy Spirit

In its Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, the Vatican Council reminds us that ‘conscience’ is ultimately a judgment made from the deepest part of our being where we are in communion with God:

‘Deep within their conscience people discover a law which they have not laid upon themselves but which they must obey. Its voice, ever calling them to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, tells them inwardly at the right moment: “Do this. Shun that.” For people have in their hearts a law inscribed by God. Their dignity lies in observing this law, and by it they will be judged. Conscience is one’s most secret core and sanctuary. There, people are alone with God whose voice echoes in their depths. By conscience, in a wonderful way, that law is made known which is fulfilled in the love of God and of one’s neighbour. Through loyalty to conscience Christians are joined to other people in the search for truth and to the right solution to so many moral problems which arise both in the life of individuals and from social relationships. Hence, the more a correct conscience prevails, the more do persons and groups turn aside from blind choice and try to be guided by the objective standards of moral conduct. Yet it often happens that conscience goes astray through ignorance which it is unable to avoid. It does not thereby lose its dignity. This cannot be said of the person who takes little trouble to find out what is true and good, or when conscience is by degrees almost blinded through the habit of committing sin’(n. 16, quoted Catechism n. 1776).

The Council continues:

‘People’s dignity requires them to act out of conscious and free choice, as moved and drawn in a personal way from within, and not by blind impulses in themselves or by mere external constraint. People gain such dignity when, ridding themselves of all slavery to passions, they press forward towards their goal by freely choosing what is good, and by their skill and diligence, effectively secure for themselves the means suited to this end. Since human freedom has been weakened by sin, it is only by the help of God’s grace that people can give their actions their full and proper relationship to God’(n. 17).

It the Declaration on Religious Freedom, the Council has this to say:

‘It is by personal assent that people must adhere to the truth which they have discovered. Furthermore, it is through their conscience that people see and recognise the demands of the divine law. They are bound to follow this conscience faithfully in all their activity so that they may come to God, who is their last end. Therefore they must not be forced to act contrary to their conscience. Nor must they be prevented from acting according to their conscience, especially in religious matters’(n. 3, quoted Catechism n. 1782).

We turn once again to the Encyclical of Pope John-Paul II, The Splendour of Truth, where we read:

‘In the depths of our conscience we detect a law which we do not impose on ourselves, but which holds us to obedience. Always summoning us to love good and avoid evil, the voice of conscience can when necessary speak to our heart more specifically: “do this, shun that.” For we have in our heart a law written by God. To obey it is our very dignity as persons; according to it we will be judged’(n. 54).

‘Conscience is the witness of God himself, whose voice and judgment penetrate the depths of the human soul, calling us powerfully yet gently to obedience’(n. 58). ‘Moral conscience does not close us human beings within an insurmountable and impenetrable solitude, but opens us to the call, to the voice of God. In this, and not in anything else, lies the entire mystery and the dignity of the moral conscience: in being the place, the sacred place, where God speaks to us’(n. 58).

The difference between conscience and the super-ego

The following is a diagram by W. Glaser (see Theological Studies 1971, page 38)

Super-ego Conscience

commands that an act be perform- invites to action, to love, and, in

ed for approval, in order to this very act of other-directed

make oneself lovable, accepted; commitment, to co-create self-

basis is fear of love-withdrawal. value.

introverted: the thematic centre extroverted: the thematic centre

is a sense of one’s own value. is the value which invites;

self-value is concomitant, and

secondary to this.

static: does not grow, does not dynamic: an awareness and sen-

learn; cannot function creatively sitivity to value which develops

in a new situation; merely and grows; a mind-set which can

repeats a basic command. function in a new situation.

authority-figure oriented: value-oriented: the value or

not a question of responding to disvalue is perceived and re-

a value, but of ‘obeying’ sponded to, regardless of whether

authority’s command ‘blindly’. authority has commanded or not.

‘atomised’ units of activity individual acts are seen as a part

are its object. of a larger process or pattern.

past-oriented: future-oriented: creative;

primarily concerned with sees the past as having a future

cleaning up the record and helping to structure this

with regard to past acts. future as a better future.

urge to be punished and thereby sees the need to repair by struc-

to earn reconciliation. turing the future orientation to-

toward the value in question

(includes making good past harms).

rapid transition from severe a sense of the gradual process of

isolation, guilt-feelings etc growth which characterises all

to a sense of self-value dimensions of genuine personal

accomplished by confessing development.

to an authority figure.

possible great disproportion experience of guilt proportionate

between guilt experienced to the im-portance of the value in

and the value in question; question, even thought authority

extent of guilt depends more may never have addressed this

on weight of authority-figure specific value.

than on importance of the

value in question.

Glaser goes on to state (page 39):

‘Too much theory and practice in the Church arises from data whose source is the super-ego. Many problems can be traced to a failure to recognise the nature, presence and power of the super-ego. This is a situation which can be overcome and should no longer be tolerated.’

Church authority is meant to be a help to the formation of conscience

Cardinal John Henry Newman in his last major writing, A Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, writes:

‘The sense of right and wrong, which is the first element in religion, is so delicate, so fitful, so easily puzzled, obscured, perverted, so subtle in its argumentative methods, so impressible by education, so biased by pride and passion, so unsteady in its course, that, in the struggle for existence amid the various exercises and triumphs of the human intellect, this sense is at once the highest of all teachers, yet the least luminous; and the Church, the Pope, the Hierarchy are, in the divine purpose, the supply of an urgent demand.’

In the Declaration on Religious Freedom, the Vatican Council writes:

‘In forming their consciences the faithful must pay careful attention to the sacred and certain teaching of the Church. For the Catholic Church is by the will of Christ the teacher of truth. It is her duty to proclaim and teach with authority the truth which is Christ and, at the same time, to declare and confirm by her authority the principles of the moral order which spring from human nature itself.’

Note the reference to the ‘certain’ teaching. As we noted in discussing dogma, not all Church teaching is certain. Note, too, that the church’s teaching is at the service of conscience. It is not meant to bypass it or to over-ride it.

Cosgrave writes as follows in the article already referred to (page 35):

‘While numbers do not and cannot make an action right or wrong, they can and do indicate the degree of acceptance or rejection a specific teaching receives among the people to whom it is directed: general acceptance shows a general perception of the truth and reasonableness of the teaching; widespread rejection indicates a failure to perceive that truth and reasonableness. In the latter case, it will be incumbent on the teaching authority, either to present more convincing case for its teaching, so that more, and ideally all, can see its truth and reasonableness, and accept it; or, if this is not possible, to undertake the painful task of re-examining the official teaching, so as to arrive at and proclaim a different position, whose truth and reasonableness can be made evident by convincing arguments. This is not merely desirable, it is obligatory on Church teaching authorities. If it is not done, only harm can come to the community in the form of uncertainty, confusion, disagreement and conflict and, perhaps worst of all, the gradual erosion of the teaching authority of the Church.’

We conclude our reflections with the following caution from Newman in his ‘Certain Difficulties felt by Anglicans’:

‘Conscience is the voice of God … Conscience is not a judgment upon any speculative truth, any abstract doctrine, but bears immediately on conduct, on something to be done or not to be done … hence conscience cannot come into direct collision with the Church’s or the Pope’s infallibility, which is engaged on general propositions, and in the condemnation of particular and given errors. Next, I observe that, conscience being a practical dictate, collision is possible between it and the Pope’s authority only when the Pope legislates, or gives particular orders, and the like. But a Pope is not infallible in his laws, nor in his commands, nor in his acts of state, nor in his administration, nor in his public policy. If conscience is to prevail against the voice of the Pope, it must follow upon serious thought, prayer and all available means of arriving at a right judgment on the matter in question … The onus of proof is on conscience. Unless a person is able to say to himself, as in the presence of God, that he must not and dare not act upon the injunction of the Pope, he is bound to obey it.’