Paul 4. Romans : Theology

Saint Paul: Andrei Rublev

'Be transformed by the renewing of your minds'(12:2)

Today's generation demands a renewal of theology if Revelation is to connect and engage.

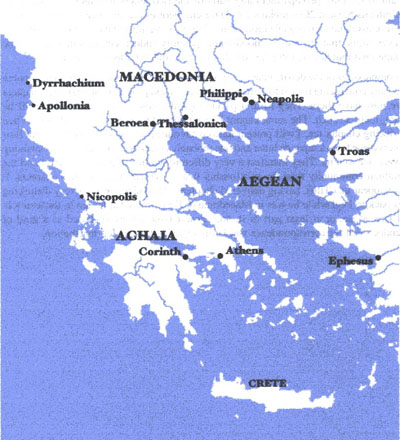

55AD 'Paul left Ephesus for Macedonia'(Acts 20:1)

• Mission in Macedonia during which he wrote the Second Letter to the Corinthians.

56AD 'When he had gone through those regions, he came to Greece where he stayed for three months'(Act 20:2).

• During this three months (winter 56-57) he composed the Letter to the Romans.

In no other letter are we as conscious as we are here of listening to the outpouring of the heart of a Christian Jew who is grateful for his Jewish heritage and grateful also that, through Jesus, he has come to see how God wills the revelation given to Abraham and to Moses to reach out to the whole world, and so bring about the fulfilment of God’s promises. Paul’s focus is on the universality of God’s plan of salvation, and the critical importance of Jews and non-Jews living in communion in the love of Christ, respectful of each other and accepting each other with all their differences. This is one of Paul’s abiding convictions and it admitted of no compromise. Paul is keen to demonstrate that there is a power, a presence, a love and a Spirit offered in Jesus which enables the Jews in the Roman community, in true fidelity to the Torah, to go beyond its limits and to attain its goal. His focus is on God’s love, the love seen in Jesus. the love that is God’s gift experienced in the Christian community, the love which draws Jews and Gentiles into communion. He wants to show that this love is the fulfilling of the Torah, and that a faithful Jew can be fully obedient to God by belonging to the Christian community, and by looking to Jesus to learn from him what it means to love with God’s love, with the love of Him who loves all people without distinction of race.

Paul claims to have ‘received grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith among all the Gentiles, including yourselves who are called to belong to Jesus Christ’(1:5-6).

‘The Gospel is the power of God for salvation to everyone believing, to the Jew first and also to the Greek’(1:16).

‘God justifies the person who has the faith of Jesus’(3:26).

‘God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us’(5:5).

‘Thanks be to God that you have become obedient from the heart to the form of teaching to which you were entrusted’(6:17).

‘We are slaves not under the old written code but in the new life of the Spirit’(7:6).

‘To set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the Spirit is life and peace’(8:6).

‘There is no distinction between Jew and Greek; the same Lord is Lord of all and is generous to all who call on him. For“Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved.” But how are they to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him? And how are they to proclaim him unless they are sent? As it is written, “How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!”’(10:12-15)

‘If some of the branches were broken off, and you, a wild olive shoot, were grafted in their place to share the rich root of the olive tree, do not boast over the branches. If you do boast, remember that it is not you that support the root, but the root that supports you.’(11:17-18).

‘God has the power to graft them in again.’(11:23).

‘O the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

“For who has known the mind of the Lord? Or who has been his counsellor?”(Isaiah 40:13)

“Or who has given a gift to him, to receive a gift in return?”(Job 41:3)

For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be the glory forever. Amen.’(11:33-36).

Moral Theology

Morality is the fruit of God’s liberating love: it is Christ living in us. It is impossible to live a moral life free from sin without this gift, even with the law. This gift is, however, offered to all, without distinction, Jew and Gentile alike. Paul does not argue like the Stoics for the logic of his positions, or attempt to show that they are inherently consistent. Nor does he present Christian morality as something that we can live by our own efforts so long as we are good-willed and rational. He invites people to faith. He invites people into the Christian community. He invites us to belong to Christ and to experience his indwelling Spirit. He shows what fruit can come from such a union, fruit that without such a union is quite impossible. His prayer is not for greater rationality and more responsible self- sufficiency, but that ‘the power of Christ’(2Corinthians 12:9) may dwell in us so that our lives will be lives of ‘righteousness’.

‘I appeal to you therefore, brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.’(12:1-2).

‘Do not claim to be wiser than you are.’(12:16).

Paul speaks of ‘the grace given me by God to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles in the priestly service of the gospel of God, so that the offering of the Gentiles may be acceptable, sanctified by the Holy Spirit.’(15:15-16).

‘I am going to Jerusalem in a ministry to the saints; for Macedonia and Achaia have been pleased to share their resources with the poor among the saints at Jerusalem … When I have completed this, and have delivered to them what has been collected, I will set out by way of you to Spain … Join me in earnest prayer to God on my behalf, that I may be rescued from the unbelievers in Judea.’(Romans 15:25-26, 28, 30-31).

Pope John XXIII

Opening address at Second Vatican Council, October 11th 1962

‘Our task is not merely to hoard this precious treasure, as though obsessed with the past, but to give ourselves eagerly and without fear to the task that the present age demands of us – and in so doing we will be faithful to what the Church has done in the last twenty centuries. So the main point of this Council will not be to debate this or that article of basic Church doctrine that has been repeatedly taught by the Fathers and theologians old and new and which we can take as read. You do not need a Council to do that. But starting from a renewed, serene and calm acceptance of the whole teaching of the Church in all its scope and detail as it is found in Trent and Vatican I, Christians and Catholics of apostolic spirit all the world over expect a leap forward in doctrinal penetration and the formation of consciences in ever greater fidelity to authentic teaching. But this authentic teaching has to be studied and expounded in the light of the research methods and the literary formulations of modern thought. For the substance of the ancient deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another. And it is to this latter that careful and where necessary patient consideration must be given, everything being measured according to the requirements of a teaching authority that is predominantly pastoral in character’.

On the Jews (shortly before his death)

‘We realize now that many, many centuries of blindness have dimmed our eyes, so that we no longer see the beauty of your chosen people, and no longer recognize in their face the features of our first-born brother. We realize that our brows are branded with the mark of Cain. Centuries long has Abel lain in blood and tears, because we have forgotten your love. Forgive us the curse which we unjustly laid on the name of the Jews. Forgive us that with our curse we crucified you a second time.’

Pope John XXIII on his deathbed

‘Today more than ever, certainly more than in previous centuries, we are called to serve mankind as such, and not merely Catholics; to defend above all and everywhere the rights of the human person, and not those merely of the Catholic Church. Today's world, the needs made plain in the last fifty years, and a deeper understanding of doctrine, have brought us to a new situation, as I said in my opening speech to the Council. It is not that the Gospel has changed: it is that we have begun to understand it better. Those who have lived as long as I have were faced with new tasks in the social order at the start of the century; those who, like me, were twenty years in the East and eight in France, were enabled to compare different cultures and traditions, and know that the moment has come to discern the signs of the times, to seize the opportunity and to look far ahead.’

Bernard Lonergan SJ

‘Religion in an era of crisis has to think less of issuing commands and decrees and more of fostering self-sacrificing love that alone is capable of providing the solution to the evil of decline and of reinstating the beneficent progress that is entailed by sustained authenticity.’ ‘Just as theology in the thirteenth century followed its age by assimilating Aristotle, just as theology in the seventeenth century resisted its age by retiring into a dogmatic corner, so theology today is locked in an encounter with its age. Whether it will grow and triumph, or whether it will wilt to insignificance, depends in no small measure on the clarity and accuracy of its grasp of the external cultural factors that undermine its achievements and challenge it to new endeavours’(Second Collection page 58).

John Henry Newman

‘It seems hard that those who work and who therefore, as men, must make mistakes, should not have those mistakes put to the score of their workings, and thanked for the work which others do not.’

Karl Rahner SJ

‘Theology is anything but a settled, dry-as-dust affair; it offers ever new challenges to mind and heart, if we have but the courage to take them up, and both the courage and the humility to retrace our steps as soon as we become aware of having erred. No one who really believes that theology, like any science, can be confronted with real problems demanding better, clearer, more comprehensive and possibly simpler solutions, will begrudge seeing such problems raised. Nor, should a proposed solution prove inadequate or even erroneous, will he imagine that the role of the fraternal critic is the same as that of the ecclesiastical censor. To pose questions about some reality which is the object of a defined doctrine is not tantamount to doubting or contesting that doctrine; it is the unavoidable business of the theologian who refuses to find comfortable support for his own mental laziness in the definitions of Denzinger.’(Inspiration in the Bible).

‘We Christians are on the whole too blind or too lazy to recognise the latent ‘Christianness’ in the history of human existence, or religion in general and of philosophy. Unconsciously we are often guilty of living in the selfish narrow-mindedness of those who think their knowledge is more valuable and more blessed with grace if it is possessed only be a few; we rather foolishly think that God himself only makes an impression on men with his truth when we have already made an impression on them with our thematic and sociologico-official and explicit form of this truth.’(‘Philosophy and Theology’ in Theological Investigations VI)

‘We Christians today readily admit that other Christians live in the grace of God, that they are filled with the Holy Spirit, are justified, are children of God and are united with Jesus Christ, and that in the ecclesial and social dimension too they are united in very many respects with all other Christians and with all other denominations. Without doubt, then, much more and much more fundamental things unite Christians of the different churches than divide them’

(‘Foundations of Christian Faith’ page 356).

‘Because of the supernatural existential, produced in the human soul by God’s real offer of his grace, the strivings of the human spirit which all people experience are the strivings of elevated nature. Even the non-Christian and the atheist have an experience of grace in the love, the longings, the emptiness, the loneliness, which accompany a genuine loving commitment to real human values. In their fidelity to true human values, despite discouragement and disillusionment, they are serving the “absent God”, whom they experience through his grace, although they cannot find him in the world with which they deal explicitly through their objective concepts.’

‘Presumably there is something like a straightforward ‘discernment of spirits’ which will help us get through on questions of orthodoxy. If a theologian attempts to interpret positively the official teaching of the Church without rejecting this flatly or from top to bottom; if he does not merely express his critical reservations, but stands up positively and seeks lovingly to win people for faith in God and in Jesus Christ; if he is not merely a critic, but a herald of the faith; if, without fuss, he shares and helps to sustain the life of the Church: then the orthodoxy of his opinions may be presumed until the contrary is conclusively proved. Whatever corrections or clarifications of his teaching may become necessary can safely be left to the work of theology itself and to the future. There is no need of an immediate threat of excommunication’(The Shape of the Church to come).

‘Within theology itself there must be philosophising, or, more simply, there must be radical thought, radical questioning and radical confrontation. That is at bottom the most edifying theology. For a theology of this kind needs to keep in mind its task of serving the Gospel of Christ; consequently it must not become an ‘academic’ curiosity, using the data of faith as objects of speculation without being existentially involved. On the contrary. ‘Philosophising’ goes on in theology as long as man radically confronts the message of the faith with his understanding of existence and of the world, for it is only in this way that the saving message can speak to the whole man as a free person.’ (from “Philosophy and Theology” in Theological Investigations VI page 83).

‘How much do our statements from university podiums, from pulpits and from the holy tribunals of the Church have such a ring that we fail to perceive clearly that these statements are virtually trembling with the last bit of the creature’s modesty that knows that all speech can be only the last moment before the holy silence that fills even heaven itself with the clear vision of God face to face’(Communio 1984, page 406).

‘I would like only to testify to the experience that theologians are only truly theologians when they do not think complacently that they are speaking with transparent clarity, but are frightened at the swinging of the analogy between Yes and No over the abyss of the inconceivability of God, and at the same time experience it as holy and testify to it. I would like only to confess that I, as a poor theologian, in all my theology, think too little of this analogous character of all my statements. We talk too much about the subject and ultimately forget in all this talking the subject itself’(Communio 1984, page 407).

Every generation is called on to ‘do theology’, that is to say to seek to discover at ever greater depths the meaning of revealed truth. As a science, theology is systematic and endeavours to be consistent. It is also an art, for understanding follows on the wonder and mystery of revelation. Doing theology, humbly and honestly is one contribution that each generation makes to the next in handing on the good news of Jesus’ revelation.