Catechism : The Creed

Chapter 1 Part 1 : Believing and knowing

The first part of the Catechism (n. 26-1065) focuses on the Apostles’ Creed, and the First Section (n. 26-184) is entitled ‘I Believe’ – ‘We Believe’. We begin our commentary by examining what it is to ‘know’, and what it is to ‘believe’. In essence to ‘know’ is to acknowledge something as true based on evidence; to ‘believe’ is to acknowledge something as true based on trust.

Knowledge and Belief

As a new-born baby we know nothing. Our waking hours consist in a stream of sensations (smelling, tasting, seeing, hearing, touching) and feelings (wanting food, sleep, touch, picking up the moods of our mother).

Knowing needs a question and an inquiry that concludes with a satisfactory answer. We begin to know quite young. At first someone else asks the question, and, provided it is uncomplicated and requires no double checking, we are able to investigate and achieve an answer. ‘No, Mummy, the car is not in the driveway’; ‘Yes, Mummy, the baby is awake, but she is not crying’. Mum is rightly confident in the answer and so is the child.

Then, as every parent knows, we start asking our own questions. Our parents learned the art of providing part answers that satisfied us for the time being. We weren’t old enough to know that their response did not really provide a satisfactory answer to our question. It left further questions to be explored, but we did not know this at the time. However, while in simple, uncomplicated matters we grew in knowledge, most of the responses we gave as a small child were learned from our parents and from others we trusted. We didn’t really know, we believed.

It might surprise us to learn that most of the things we think we know, we in fact believe. I might claim to know that the earth goes around the sun, whereas in fact my judgment is based on insights and judgments made by others. I’d be foolish not to believe it, since everything I have come to know supports this judgment. At the same time I haven’t taken the trouble (you may have!) to carry out for myself all the complicated physics and maths needed to establish the fact.

In his book Method in Theology (Darton, Longman and Todd, 1971, page 43), Bernard Lonergan writes:

'Human knowledge is not some individual possession but rather a common fund, from which each may draw by believing, to which each may contribute in the measure that he performs his cognitional operations properly and reports their results accurately. A person does not learn without the use of his own senses, his own mind, his own heart, yet not exclusively by these. He learns from others, not solely by repeating the operations they have performed but, for the most part, by taking their word for the results. Through communication and belief there are generated common sense, common knowledge, common science, common values, a common climate of opinion. No doubt, this public fund may suffer from blindspots, oversights, errors, bias. But it is what we have got, and the remedy for its short-comings is not the rejection of belief and so a return to primitivism, but the critical and selfless stance that, in this as in other matters, promotes progress and offsets decline.'

There is so much to know. Even if we were possible, we would be foolish to reject all belief. The whole scientific endeavour would collapse if scientists accepted only what they themselves had established from their own resources.

Objectivity in knowledge requires more that logic. It is the fruit of being an authentic subject

We grow in knowledge to the extent that we are committed to the following processes (following Bernard Lonergan SJ):

1. We are attentive to our experience, both as regards the objects that we experience and ourselves as the subject consciously having the experience.

2. We are intelligent in the sense that we have engaged our intelligence, looking for insights that might help us discover answers to the questions we ask about what we are experiencing.

3. We are reasonable in that we have checked our insights till we are satisfied that we have looked at things from every relevant angle and our questions have been satisfactorily answered.

4. We are responsible in that we make a judgment based on the evidence about how things really are, as distinct from how they might appear to be or how we might like them to be.

Every step along the way we experience a spontaneous, dynamic drive, moving us to experience things, people, situations, and to want to understand what it is we are experiencing. When an idea occurs to us that might lead to understanding, we experience a spontaneous, dynamic drive to check it, to make sure. At times we have to look elsewhere for an answer. At other times we think we are on to something but more questions arise and we have to follow these up till we run out of relevant questions. When all our questions have been satisfactorily met, we experience a spontaneous, dynamic drive to conclude our inquiry. On the evidence we conclude that our understanding is true or false. Sometimes we are certain of our conclusion. Sometimes the best we can manage is a level of probability.

It is essential that we reflect carefully on these various steps. When we do we find that there are two poles to each step of our inquiry.

In one and the same act we experience something (what we could call the objective pole of the experience), and we experience ourselves having the experience (what we could call the subjective pole of the experience). Sometimes we reflect upon ourselves. When we do this we are, in the same act, conscious of ourselves as the subject doing the reflecting and the object of the reflection.

In wanting to understand what we are experiencing, we are, in one and the same act, conscious of ourselves as the inquiring subject and of the thought that we are examining as the object of our inquiry.

In so far as our inquiry reaches a conclusion because the evidence has been satisfactorily tested, we are, in one and the same act, aware of the conclusion we have come to, and conscious of ourselves as the subject forming the judgment.

In other words, our intelligence is in touch with reality. We are able, to varying degrees, to discover the way things really are. We are able to know.

It is not easy to work our way thoroughly and honestly through these steps.

We can be inattentive to what we experience. We can become uninterested, insensitive, content to live in a world dominated by our feelings.

We can muddle along from one experience to the next without making the effort to understand what is going on or to integrate our experience into our life in a meaningful way. We can opt out of the concentration, discipline and perseverance needed to pursue truth, and instead we can choose to dissipate our energy by living a distracted life, a dissipated life. We can lapse into a stupour (‘veging out’ far too often, till it becomes a habit). We can substitute what we pick up from talk-back radio for the effort required to check things out.

We can misunderstand, mis-take. We can make no effort to check our assumptions. We can wallow in our prejudices. We can lock ourselves into an ideology, conform to habit or trendy opinion. By not questioning the first thought that comes into our mind we can work from oversights, illusions, rationalisations. We can be silly, gullible, careless.

We can jump to conclusions, prejudge a situation or a person, and so fail to connect with what is real, fail to arrive at the truth.

Again and again we come to know that our spontaneous and dynamic drive to know does connect us with what is real, when we allow ourselves to reach beyond our ‘comfort zone’ and pursue the truth whatever the cost.

In matters that are significant our grasp of truth is rarely complete. Rather it is a progressive extension and refinement of our grasp of reality by a progressive extension and refinement of the self-transcendence that moves us from a world of experiencing to a world of knowing.

The modern explosion of knowledge brings its own problems. Rahner reminds us:

‘The enormous amount of knowledge offered today leads to uncertainty. The speed at which sciences are racing into the future makes every individual element of knowledge already acquired appear to be temporary and subject to revision’(Theological Investigations volume XXI, page 130).

‘The enormous amount of knowledge offered today leads to uncertainty. The speed at which sciences are racing into the future makes every individual element of knowledge already acquired appear to be temporary and subject to revision’(Theological Investigations volume XXI, page 130).

Knowing is not something arbitrary. It is not like tossing a coin. To the extent that our search for the truth is authentic, we can be confident that our intelligence is connecting us with what is. As already noted, objectivity in knowledge requires more than logic. It is the fruit of being an authentic subject, including the honest sharing of our experiences, our understanding and our judgments.

Belief

We say we ‘believe’ when we accept something as true because we trust.

There are many layers of belief. There is the belief that a child has in tooth fairies or in Santa Claus. As children we are not in a position yet to ask questions. We trust our parents and so we believe.

As adults there are many things that we believe (hold as true), because we trust experts in the field and we find that our belief is supported by the constant reinforcement that results from acting on our belief. As already noted, without belief the scientific community would grind to a halt.

Conscious belief always is the result of a choice. Living would be impossible if we doubted the accuracy of every measuring line and every street directory, even though we haven’t worked it all out for ourselves. At the same time we don’t follow our beliefs blindly. We are dealing with probabilities, and while this ruler or this directory could be wrong, it is highly unlikely, and we simply do not have the time or the knowledge to check everything for ourselves. In some matters we have grounds for certainty, in other matters we accept something as probably true, in yet other matters we accept something as a working hypothesis until further evidence enables us to refine our judgment.

We need constantly to examine our beliefs and to be diligent in discovering and correcting any carelessness, credulity or bias. When our trust has proved right over and over again, it is reasonable to continue our choice to believe.

When is it reasonable to believe?

It is not always sensible to believe. The person whom we believe should be worthy of trust. It is naïve and often foolish to believe someone who is untrustworthy. Even if a person is generally trustworthy, it is reasonable to accept their word as true only in areas where they are knowledgeable. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for ‘experts’ to claim authority in areas beyond their expertise. There are problems, too, with hearing things second and third hand. We would be wise to believe only when we are confident that what we are believing does in fact come from the knowledgeable and trustworthy expert who is claimed to have said it.

From our side there are two important criteria for reasonable believing. The first is that what I believe must be consistent with what I know in other areas. We can tentatively hold hypotheses that appear contradictory while we search for a higher viewpoint, but truths (judgments about the way things really are) cannot contradict. Sadly, it is not uncommon for us to compartmentalise our ‘knowledge’ and not examine the connections between things. We are capable of holding as true matters that are, in fact, contradictory.

Another criterion is the fruit in our lives of believing. We cannot know everything through independent personal investigation. To live we need to accept many things as true on the word of another who knows. If, through believing, I find myself becoming more attentive, more thoughtful, more reflective, more truthful, more responsible, and more loving, my believing would seem to be reasonable. If things go the other way, it is likely that my believing is misplaced.

Believing plays an essential role in knowledge

The word ‘believe’ goes back to the Anglo-saxon roots of the English language where ‘lieve’ is an older spelling of ‘love’. To ‘believe’ is ‘to-be-in-love’. It is love that motivates a person to engage on the demanding process of knowing. Where love is absent we are less likely to be attentive, intelligent, reasonable and responsible (see under 2 above).

Since to believe is to accept something as true based on reasonable trust, there is value in reflecting on the role played by love in relation to trust and so belief. When we begin the Creed with the words ‘I believe’ we are speaking of what we have come to hold as true because of our experience of love.

Chapter 1 Part 2 : I believe in God

In the Catholic Catechism n. 26 we read: ‘Faith is our response to God, who reveals himself and gives himself to us, at the same time bringing us a superabundant light as we search for the ultimate meaning of life.’

Chapter One (n. 27-49), which is the topic of this chapter as well, looks at this search, and begins with a quote from the Second Vatican Council: ‘Human dignity rests above all on the fact that we are called to communion with God. This invitation to converse with God is addressed to us as soon as we come into being. For if we exist it is because God has created us through love, and through love continues to hold us in existence. We cannot live fully according to truth unless we freely acknowledge that love and entrust ourselves to our Creator’(The Church in the Modern World, GS n. 19).

The Catechism goes on to speak of the ambiguities and paradoxes that we see in the human religious response to God. It is important that we acknowledge these ambiguities and paradoxes. They make us respectful of religious cultures and language that differ from our own. Without in any way lessening our gratitude for what we have been shown as disciples of Jesus, it helps to keep us open to the limits of our own viewpoint, and to be open to learn from the many rich insights that are part of our heritage as human beings.

We might begin by asking ourselves: What are people talking about when they say they believe in God?

1. God invites everyone to enjoy divine love-communion

As far back as our records go, people who experienced the sea have been moved with a profound reverence for what they have experienced and have found ways of worshipping the ‘god’ of the sea. The name given to the sea-god varies from language to language. The experience, too, varies. Sometimes the aspect of power dominates. Sometimes it is the amazing variety of moods that has captured people’s imagination. Sometimes fear seems to play a huge role, and sometimes faith is put in magical rituals and rites that are believed to win the favour and avert the anger of the powerful sea-god. Peoples channel their experience into hundreds of different understandings and practices, but I suspect that there is one fundamental experience that lies at the basis of the various religious responses, and it is a sense of communion that people experience. In ways that are too profound for understanding, we sense that there is a connection between us and the sea: that somehow we belong to each other. When we experience the various moods of the sea, we experience the various moods of our own heart. Tragically, human frailty, including hunger for security and power, can obscure this primal experience of communion, and the religions of the world witness to dreadful human behaviour done in the name of worshipping the sea-god. However, if we can abstract from these, I suspect that believing in the sea-god, by whatever name, is acknowledging a profound sense of wonder and awe, and, even more importantly, an experience of communion.

Parallels can be drawn with people’s experience of a grove of trees, a spring, a mountain, a storm, light and darkness, birth and death, bird and animal life, the seasons, the many and varied harvests, mother, father, sexual union, childbirth, dancing, music, painting and the myriad human experiences that have given rise to worship. Since there is no obvious connection between the sea and a grove of trees, throughout human history the norm has been polytheism. People have had their favourite ‘god’, but have sensed in various ways a communion with the mysterious, awe-inspiring, ‘gods’(divine presences) in all their experiences.

Some people, and consequently some cultures, have come close to monotheism, that is, to the amazing insight that the mysterious divine presence with whom they experience a profound communion is the one God present and revealed in different ways in all the varied experiences indicated in the previous two paragraphs. Ancient Judaism is sometimes spoken of as a monotheistic religion, and there are indications in the ancient texts of a gradual movement towards monotheism. However, their writings give no evidence of the kind of profound respect for other peoples that is surely essential to genuine monotheism. If one genuinely believes that it is the one God who is at the heart of everything, and is expressed and revealed through everything, then one would not disrespect others just because they are different from ‘us’. We would still have to deal with error – our own and other people’s, but surely monotheism includes the insight that everything is fundamentally an expression of the one Source and so is fundamentally sacred. The same failings of classic Judaism can also be seen in the behaviour of others who claim to be monotheistic, including among the followers of Jesus of Nazareth, or Muhammad.

At the same time, history is full of genuine monotheists who have recognised that the communion which they experience at the heart of their varied experiences is with the one sacred Presence who is at the heart of, and at the same time transcends, everything. An outstanding example is Jesus of Nazareth who refused to live within the limited thinking and practice of the religion of his contemporaries, and who gave expression to his communion with God in a life of love that was all-embracing. Those among Jesus’ followers who have grown to share Jesus’ experience have done the same.

In the light of Jesus’ example, perhaps we could answer the question posed here by saying that, for a true monotheist, to believe in God is to believe that everything belongs to everything else, because everything that exists is held in existence by the one Source and is part of an explosion of love radiating from this Source and revealing different aspects of the Source. If we use the word ‘grace’ for the action of this Source, to believe in God is to believe that grace acts like gravity, drawing everything to everything else. Paradoxically, grace is also experienced as a centripetal force drawing everything into the beyond – into communion with this Source who is immanent in creation but who transcends it, who is, in the words of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, ‘the heart and the beyond of everything’. To believe in God is to believe that genuine religious experience is the experience of being drawn into communion with everything that exists in such a way as to be drawn through everything and beyond everything into communion with the One who is the Source of everything that exists – into communion with the Source, one name for which is God.

In light of the primal human connection with one’s mother, it is not surprising that the image of the mother goddess is central to many cultures. One thinks of Cybele, the mother goddess of Anatolia, whose worship found its way into Greece in the fifth century BC, and into Rome in the second century BC. Examples from other cultures can be multiplied. Is the movement to the father god an indication of the drifting away from the experience of communion to an emphasis on power, control and fear? If there is any truth in this, Jesus’ calling God by the intimate word ‘Abba’ and his revealing God as love was his way of drawing the patriarchal religion of his contemporaries back to their primal experience of communion.

2. Variety of Religious Experiences

The wide range of religious experiences is affirmed by the sacred scriptures of all the major religions of the world in whatever way they conceive the ultimately Real to be. It is affirmed by the Vedas and the Upanishads, the sayings of K’ung-fu-tzu (Confucius), Lao Tzu and Gautama the Buddha, by the oracles of the Hebrew prophets, the Newer Testament and the Qur’an. It is of this that the mystics of all cultures speak, as do the poets and artists and lovers of our world. Paul hints at this in his speech at Athens: ‘From one (probably meaning ‘one Source’ and referring to God) God made all nations to inhabit the whole earth … so that they would search for God, even grope for God, and find God – though indeed God is not far from any of us.’ Paul goes on to quote from Epimenedes, a sixth century BC poet from Crete: ‘For in him we move and live and have our being’(Acts 17:26-28; quoted n. 28 of the Catechism).

There are as many examples of religious experience as there are people who have longed for love. These experiences have found expression in inspired music, inspired painting, inspired poetry and inspired action: the ordinary inspired action of loving that every mother, father, aunt, uncle, teacher and nurse knows in his or her daily life.

In the history of humankind, people have always looked towards those whose lives have been particularly free from the distractions that lead to sin and whose religious sensitivity led them to an attractive wisdom. Every people has its saints, its wise men and women who have been especially sensitive to the inspiration of the ‘Spirit of God’, and who have responded creatively and often heroically to this inspiration, living lives that have mediated God in a wonderful way to others. They have been a ‘word of God’ to their contemporaries, connecting them in a remarkable way with life, connecting them with God.

3. The Numinous and the Mystical: God's 'Word' and God's 'Spirit

The Hebrew Scriptures (and readers who are familiar with other ancient religions will recognise the same phenomenon) speak of the religious experience that comes through God’s ‘word’. God spoke to them through the prophets (among whom Moses had a special place) and through nature and history. This is called the ‘numinous’ dimension of religious experience (from the Latin ‘nuo’, meaning ‘to nod’). God revealed his presence and his will through his ‘Word’.

Judaism has high regard for the prophetic for it treasures the words received from those who were judged to have been especially sensitive to the divine presence. Obedience and submission to God’s will are of central importance. Islam shares this respect for the numinous dimension of religious experience, and elements of this can be found in other religions.

Some forms of Buddhism concentrate on the revelation of the transcendent God that is mediated through the movements of a person’s mind and heart. This is called the ‘mystical’ dimension of religious experience, for the focus is on an inner enlightenment and transformation that cannot be adequately expressed, and remains ‘mysterious’. Buddhism gives priority to this inner enlightenment. We find it in Judaism where it is spoken of as an experience of God through his ‘Spirit’ moving in our hearts.

On the one hand, Christianity is like Judaism and Islam in that it takes the world and its history seriously, recognising that God is present in the world speaking his ‘Word’ to us through nature and through the events of our life. To encounter God we must listen humbly and at depth to God’s ‘Word’ speaking to us from the heart of creation and in the events of our history. We will have more to say on this when we come to speak of Christianity, for Jesus’ disciples came to see him as not just speaking God’s ‘Word’ but as incarnating God’s ‘Word’ in his person (John 1:14).

On the other hand, Christianity is like Buddhism in that its focus is on the heart. We will say more of this, too, when we come to speak of Jesus, for his disciples experienced him as having and giving the ‘Spirit’ without reserve (John 3:34), a ‘Spirit’ that he shares with his disciples, enabling us to experience in our hearts the enlightenment and transformation that is the fruit of divine communion. As Paul writes to the Romans: ‘God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us”(Romans 5:5).

In Jesus the numinous and the mystical come together. Authentic Christianity does not neglect or consider as illusory either the outer ‘Word’ or the inner ‘Spirit’.

For Christians, God remains transcendent, so we need to be attentive to the way in which God is revealed to us in the world, and especially in Jesus (God’s ‘Word’). As in Judaism and Islam, obedience is basic. The Christian, however, is also invited to enjoy the wonderful indwelling of God revealed in Jesus and experienced as we are drawn by grace to share in his ‘Spirit’, his intimate communion with God. As in Buddhism, enlightenment, inner transformation and communion are essential dimension of religious living. We find both these elements in the opening words of John’s First Letter: ‘Something which has existed since the beginning, that we have heard and have seen with our own eyes; that we have watched and touched with our hands: the word who is life - this is our subject. That life was made visible: we saw it and we are giving our testimony, telling you of the eternal life which was with the Father and has been seen by us. What we have seen and heard we are telling you so that you too may be in union with us, as we are in union with the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ. We are writing this to you to make our own joy complete.’

The Existence of God

Since reality is intelligible, God must exist.

The Catechism speaks of ‘converging and convincing arguments’ for the existence of God (n. 31): ‘These can predispose a person to faith and help us see that faith is not opposed to reason’(n. 35). These arguments are not proofs in the mathematical or scientific sense. Nor should we look for such proofs. Most of our human experiences lie outside the range of the empirical sciences. As Karl Rahner says:

‘The natural scientists should constantly accept theology’s reminder that the world view, which is actually a part of their lives and not just something conceived by the monopolistic claims of the natural sciences, is something which cannot be determined by their natural science alone; that spirit, freedom, fidelity, love, the infinite question of existence cannot be “explained” by natural science alone’(Theological Investigations, volume XXI, page 65).

If we examine our experiences we realise that there are many things that we judge to be true without being able to demonstrate the truth in such a way as to convince others, especially if they do not want to be convinced. As the Catechism makes clear (n. 36-38), arguments for the existence of God do not demand consent. Openness to the transcendent requires ‘self-surrender’ (n. 37).

It is time to make a point that is of the most profound significance. Over and over again we discover that our inquiring mind is connecting us with reality. Again and again we find answers to our questions. If something is happening it must be able to happen, and we hope to be able to understand the processes that account for it happening. Sometimes we manage to find out. At other times the explanation evades us. But we never doubt that there is an explanation. In other words we take it for granted that reality is intelligible. The whole of our life experience (including the marvellous success of science) reinforces the correctness of approaching reality as ultimately intelligible.

However, when we ask the big question (‘How come this being exists?’), the beings that we experience (including ourselves) do not provide a satisfactory answer. I know that you exist. With the help of some knowledge of your history plus some elementary biology, I can come to know why you came into being. But when I ask how it is that you are now existing, I don’t find the answer by knowing you. It is a fact that you are. But there was a time when you weren’t. You do not have within yourself a satisfactory explanation of your being. If you did you would exist, not just in fact, but necessarily. If I want a fully satisfying explanation of your existing I have to look outside you. However, wherever I look I come up against the same problem. Everything I know exists, like you, in fact but not necessarily. It is – to use the technical word – contingent. I have learned to trust that my inquiring mind does connect me with reality. You are, so there must exist an explanation. Something accounts for you existing now. What is it?

The only conclusion we can draw is that there must exist here and now a Being that lies outside the limits of my experience and knowledge, a Being that does not require an explanation outside itself for its existence, a Being that exists, not only in fact, but necessarily, since it contains within itself a fully satisfactory explanation of its existence. Contingent reality exists because it is held in being by this necessarily existing Being. The intelligibility of reality demands the existence of the ultimate Source we call God.

That God exists is something we know. Logic requires it. However, God is not an object of direct experience or knowledge. We cannot form comprehensive concepts of God, for the Being that must exist if what we know has meaning, this Being transcends the capacity of the human mind to know, and, in that sense, remains absolutely ‘mysterious’. How we conceive God is a matter of belief, not knowledge.

5. How we conceive God is a matter of belief, not knowledge.

I am unable to give an accurate account of the images and concepts that I associated with the word ‘God’ when I was a child. As a child I believed many things that I outgrew. I believed, for example, in the existence of Santa Claus. However, when I came to the point of asking my parents whether Santa Claus actually exists, they knew I was ready to leave the magical world of childhood and hear the truth. I also believed that Adam and Eve were real people who started off the human race. It was not till much later that I came to realise that the Bible narrative is a story, not a factual record. The truths conveyed by the story are profound, but they are not on the level of fact. As for God it wasn’t till I became aware of the existence of atheists, and of the many ways in which different cultures imagine God that I had to question whether there is a God, and if so, how should I think of this God. As a child I never asked such questions. God was central to the view of life into which I was socialised, acculturated, educated, in our family and in the life of our local parish and school.

When in my late teens I looked into the question of God I realised that to deny the existence of a Being that is the ultimate Source of everything that exists (an idea expressed in the notion of ‘Creator’) is to conclude that everything I know, including myself, is ultimately unintelligible. This struck me, and still strikes me, as a rejection of what I know about myself as an inquiring being, and the partial, but obvious, success of sustained inquiry (see Chapter 1a). Science is a standout example of successful inquiry and discovery of the truth, and we are forever growing in our knowledge of the human psyche and of communities thanks to advances in psychology and the social sciences. Since the process outlined above continues to connect me with what is real, and since the spontaneous drive to inquire knows no limit, surely there are answers to my questions even if they lie beyond my ability to comprehend. Since the world, as far as I am able to ascertain, is fundamentally intelligible, surely things must ultimately make sense.

As already stated I came to the conclusion that God, in the sense of a necessarily existing Being that explains the existence of the world that I know, must exist. In drawing this conclusion I am supported by others who have reached the same conclusion, and my conclusion is reinforced by my experience, but ultimately it is based on trust of intelligence and reason. Other people (atheists) choose differently. It is up to them to explain the reasons supporting their choice. To my mind in opting for atheism they are, however unwittingly, distrusting the spontaneous, dynamic, drive of human intelligence. Sometimes they appear to be rejecting a God that I, too, reject: a God that is too small, a God that is conceived in ways that offend reason. I will come back to this shortly. Still others (agnostics) find the topic too difficult and choose to live their life without exploring the question of the existence of God. It seems to me that they can do this only by leaving aside too much of what makes life worthwhile, and by not putting enough trust in the dynamism of the human spirit in its questioning and in its quest for truth.

Faulty concepts of ‘God’

There are many concepts of ‘God’ that are handed down in the intimacy of the family and in the public life of most cultures. These concepts arise from our desire to make sense of experience. Some concepts express true insight and stand up to careful investigation; others are the result of oversight, and express a misunderstanding that upon careful reflection should be rejected. If we find accurate and inaccurate concepts in all other areas of human thinking, we should not be surprised to find that concepts of ‘God’ not only vary from culture to culture and from person to person, but that they represent a mixture of insights and oversights, of understanding and misunderstanding. After all, our concepts of ‘God’ aim to express our most profound insights into what reality ultimately is. No human concept can encompass God (see Catechism n. 42). The best we can do is to choose between contrary concepts the one that expresses better our experience, and so points us better towards the Reality that, necessarily, lies beyond our comprehension.

People differ markedly in the meanings and values that they associate with the term ‘God’. Because God is not just another thing or the sum of all things, certain forms of Buddhism rightly conceive of God as ‘No thing’. Because of the experience of relating to God in personal ways, Jews, Hindus, Christians, Moslems and many others conceive of God in personal terms.

In recent centuries, every concept of God has come under increasing suspicion. There was a time when the existence of lightning was taken as proof of the existence of the sky-god Zeus, and when the powerful, irrational feelings that at times can overwhelm us were judged to be the result of the action of vengeful supernatural beings. There was a time when victory in war was understood as proof of divine approval, while defeat demonstrated divine disapproval. For good reasons such misconceptions have been rejected. The rejection, however, has gone so far that today God appears to some to be nothing more than a category invented to cover whatever we do not yet understand. With the methodical and cumulative acquisition of knowledge in many areas, some argue that the very idea of God is a leftover from a now unacceptable naïveté.

There is no doubt that certain conceptions of God are clearly erroneous. People rightly reject a ‘God’ who is envisaged as an extra, existing outside our world and history and experience, who controls things from the outside, as it were, and is directly responsible for whatever happens, intervening in our history at will, or in answer to prayer understood as a magical power requiring a divine response. The history of religious practice, in earlier times and still in our own day, frequently reveals a so-called ‘God’ who is glorified at the expense of humanity. Some people seem to feel the need to put humanity down in order to raise God up. What is more, this ‘God’ seems in large measure to be a projection of human need and human wishful thinking, or human avoidance of the harshness of reality. Rather than face up to reality, we seem to want to invent the kind of ‘God’ to whom we can escape. Rather than face the here and now and do what we can about it, we seem to want to escape to a hereafter where everything will be as we wish things were here.

There is no point in speaking of a ‘God’ who does not require of us that we face the whole truth of our real limits, but also of the real greatness of being human. Any serious inquiry about God must be one that leads to a better understanding of and communion with our actual selves and our real world.

We are rightly suspicious of a ‘God’ who serves to support vested interests. We still hear ‘God’ being used to support the ideology of military and economic victors over the vanquished. We still experience the rich and learned, and those in possession of power of all kinds, speaking and acting in the name of ‘God’, when they are seen to be propping up their own position. Such a ‘God’ is constantly being discredited and we have no desire here to carry on the charade. Who can take seriously a ‘God’ who supports apartheid, or patriarchy, or hypocritical piety, or a refusal to accept tried and tested facts in any sphere? The treatment meted out to Galileo in the name of ‘God’ is more common than we might dare to admit. If there is value in talking about ‘God’ at all, it can only be about a God in which everything participates, and therefore a God who supports the intrinsic and inalienable dignity of everything that exists, a God of truth and of justice.

Freud worked with people with seriously dysfunctional psyches. Some of their religious attitudes were little more than a jumble of infantile illusions. His findings alert us to the need to ask ourselves how free we are of such illusions? Let us be committed to name illusions when we are fortunate or diligent enough to discover them. Any claim we might make to relate to God is worthless if our relationship fails to draw us on to maturity by clarifying our identity, deepening our intimacy and enlarging our capacity for generating the love that provides the only environment in which we and others can grow.

It is clear that all our concepts of God are precisely our concepts. They enjoy, therefore, all the strengths of human intelligence and imagination; but they also necessarily suffer from all the weaknesses. In recent centuries, some have gone beyond criticising incorrect conceptions to reject any and every conception of God as unnecessary, unhelpful and irrelevant to genuine human living and progress in knowledge. Others, while granting the need for constant refinement of our concepts of God, hold that the claim that God exists cannot be written off simply as human projection and distortion. They hold that the claim is based on an authentic, if often unreflective, response to real human experience and intelligent inquiry, and that there is a Reality, albeit one upon which we cast our projections and which we distort. They see it as a fundamental and serious error to discard the real God along with our distorted concepts.

Does rejecting the many false conceptions of ‘God’ justify the rejection of a God who, while transcending every limited being and the whole universe of limited beings, is immanent in everything? Does it justify rejection of a God who is the ultimate Reality in which everything real participates, the Being that is the reason for anything making sense, the One who is constantly sustaining, inspiring, informing and enlivening everything? Teilhard de Chardin speaks of God as ‘the Heart and the Beyond of everything’. The ‘Heart’ – because everything is held in existence, from within, by God and is a radiance of God’s Being. The ‘Beyond’ – because the closer we get to the heart of anything, the more we are invited into transcendent mystery.

Whatever errors are present in the ways in which God is envisaged, the great religions of the world are right to continue to speak of God and to explore ways of relating to this ultimate Reality ‘in whom we live and move and have our being’(Acts 17:28).

However we conceive God, ‘our human words always fall short of the mystery of God’ (Catechism n. 42). The Catechism quotes Saint Thomas Aquinas: ‘We cannot grasp what God is, but only what God is not, and how other things stand in relation to God’(Summa Contra Gentiles 1,30; Catechism n. 43).

Human concepts are adequate only within the range of our direct empirical experience. They are inadequate when we try to put words on religious experience, for, as Saint John reminds us, ‘no one has ever seen God’(John 1:18). Let us listen to Saint Justin, a second century philosopher and martyr: ‘This very name of God is not His name, for if anyone dares to claim that God has a name, he is mad. These words of Father, God, Creator, Lord and Master, are not names but words to call Him because of His Goodness and works. The word God is not a name but an approximation, which we find natural when we attempt to explain the unexplainable’(I Apologia 61,131).

Saint Gregory of Nyssa, writing towards the close of the fourth century, has the same teaching: ‘The teaching which Scripture gives us is, I think, the following: the person who wants to see God will do so in the very fact of always following Him. The contemplation of His face is an endless walking towards Him … There is only one way to grasp the power that transcends all intelligence: not to stop, but to keep always searching beyond what has already been grasped’(On The Canticle of Canticles, Homily 2,801).

In the fifth century Augustine writes: ‘If you have understood, then this is not God. If you were able to understand, then you would understand something else instead of God. If you were able to understand even partially, then you have deceived yourself with your own thoughts’(Sermon 52. vi. 16).

All the Christian mystics say the same. Let Saint John of the Cross, the sixteenth century Spanish mystic, speak for them: ‘However elevated God’s communications and the experiences of His presence are, and however sublime a person’s knowledge of Him may be, these are not God essentially, nor are they comparable to God, because, indeed, God is still hidden to the soul’ (Spiritual Canticle Stanza 1.3). ‘Since God is inaccessible, be careful not to concern yourself with all that your faculties can comprehend and your senses feel, so that you do not become satisfied with less and lose the lightness of soul suitable for going to God’(Sayings of Light and Love).

The pursuit of truth in any field will suffer from fundamental distortions if God is overlooked. Only within the perspective of ultimate Reality can we come to a proper understanding of ourselves and of our world, and to a proper way of living in it. The history of human involvement with God has its negative face, as we have already indicated. False conceptions of God continue to wreak havoc in the field of human thinking and human living. The distortions and their effects can scarcely be exaggerated. The positive face is that of the human beings we acknowledge and revere as saints. And there are hosts of them in every country, in every culture, and in every generation.

What we need here, more than anywhere, is a commitment to the quest that incorporates a careful and honest reflection on the lives of those who inspire us by the obvious fruit of their own commitment. We need also to learn from our own and other people’s mistakes to purify our concept of God by paring away ideas that have led to a distortion of a truly human life. From the goodness, the love and the overall quality of the humanity of others we can learn to respect the insights into God that inspired them. It is possible to live our daily lives without being engaged in this quest for God. However, admiration for what is beautiful, and commitment to values that demonstrably enhance our experience in the world, invite us to explore the question of God.

We cannot expect to achieve a completely satisfactory answer, for to do that we would need to have complete comprehension of everything that exists. Whenever we have a new experience, whenever someone new comes into our lives, we discover something more about reality, and so about God. However, we can continue to refine our understanding by eliminating error and learning to modify the direction of our thinking and of our choices, inspired by the wonderful people who have gone before us and who accompany us on this most exacting and most fruitful of journeys.

Yearning to belong : the experience of communion

My aim here is not to ‘prove’ the existence of God the way one might prove the existence of something by providing incontrovertible evidence that must convince anyone willing to attend to the evidence provided. The transcendent God cannot be another ‘object’ that we can put under a microscope. My aim is to invite you to attend to aspects of your own experience that might persuade you to continue to explore the mystery and not to dismiss it because it does not deal up the ready evidence that our empirically trained, scientific minds have come to expect.

I find my choice to believe confirmed by my experience of communion. I think it is our yearning for communion that drives the quest for knowledge upon which we have been reflecting. It drives all our connections with reality. Our urge to know is propelled by our longing for communion. The other remains other (I am not you), but another to which and to whom I belong. This is because everything we experience is drawn towards the Other in whose being we all participate, the One ‘in whom we live and move and have our being’(Acts 17:28).

We are attracted outwards to ever more intimate communion with the world around us, and when we experience love (the word we use for this communion), we are attracted inwards to plumb the depths of the inner world that love discloses. Our experience is that our instinctive desire to be in love (to give and receive love and to enjoy communion) connects us to reality. Our desire, however, is limitless, like our desire to know.

Nothing we directly experience can satisfy our longing for complete communion with Reality. We can choose to accept that our longing has no attainable object. Why not choose to believe that there does exist One, the One we call God, who is the reason for our limitless longing? Saint Augustine made this choice:

‘You have made us for Yourself, O God, and our hearts are restless till they rest in You’(Confessions I.1).

It is clear that our experience of love never provides full satisfaction, for there are depths to our heart and to the world that remain to be explored. The inner well seems bottomless. Our yearning seems limitless. Our longing for love seems inexhaustible. When the yearning is partially satisfied we rightly conclude that it is not something that is merely subjective. We know that we are not living in a world of fantasy. We know that we are truly in communion with something real.

However, we also know that our yearning is not fully satisfied. We long for a love that is unconditional, unrestricted, and complete. Our limited experience of love gives us reason to trust our yearning. Is it not reasonable, then, to trust that there exists a Reality that accounts for the ultimate longing which we experience, a Reality which alone can satisfy this ultimate longing? Why would our yearning be real and trustworthy in partial matters, but ultimately be unreal and deceptive? Why would we not explore the direction in which our experiences are pointing just because they point to a Reality that transcends our present experience and so remains mysterious and beyond definition? This is the Reality I am calling God.

Why not remain open to what Rahner speaks of as:

‘the one who in an incomprehensible and improbable outpouring of his love communicates himself with his inmost reality to his creatures, which, without being consumed in the fire of divinity, are able to receive God’s life, his very glory, as their own perfection’(Theological Investigations volume XXI, page 190).

Just as knowledge that comes through love takes us to a deeper appreciation of and connection with reality than knowledge that limits itself to rational logic, so in ‘knowing God’:

‘The human being can draw nigh to the incomprehensible God who remains a mystery only in loving surrender, not with a knowledge which brings the object known before the higher tribunal of knowing’. This is not ‘a regrettable remnant of a penetrating knowledge, but rather this experience constitutes the ultimate and original essence of knowledge’(Rahner ib. pages 210-21).

We learn more through love that we can ever learn from the application of logic, critically important though logic and reason are in our search for truth.

Freedom

The choice to believe in this God has necessary implications. Radically it means that my very being is received. I have nothing that I have not received. It is God who sustains me in existence and inspires everything I am and do. What I in fact do and what I in fact become depends on how I choose to receive or not receive from God. To the extent that I am open to welcome grace, my life and my living will demonstrate the creativity of being and acting in accordance with divine inspiration. To the extent that I resist inspiration, I remain distracted, out of touch, inauthentic, stunted. I am forever experiencing being drawn to transcend my present self. I am forever experiencing resistance, a wanting to hold on to what I perceive myself to be, a fear of the unknown, a complacency, the weight of habit. I am the consequence of the decisions I have made, for good and for ill.

A ‘God’ who loves and does not control

One of the key distortions that we find in the history of religions is the projection onto God of the notion of control. Control plays such a big part in society that it is not surprising that those in control and those being controlled have included the concept of control in their concept of ‘God’. Jesus saw God as ‘love’, and as we adults experience it love does not control. The word ‘love’ though inadequate, points in the right direction. The word ‘control’ does not. Thinking of God as ‘Love’ sheds light on many of the things we do know. On one level there is the reality of an expanding universe and of gravity. People speak of the experience of the ‘sacred’. We reflected earlier on the sacred sensed in a mountain, a stream, a grove of trees and the star-spangled heavens. We have come to recognise the fact that everything we know is related, at a profound level, with everything else.

There is also the reality of love between persons. If the God required by intelligence and reason is Love, so many of our human experiences of the presence of love, but also of its absence, make sense. It seems to me that it is the introduction of the concept of control that pushes intelligent people in the direction of atheism.

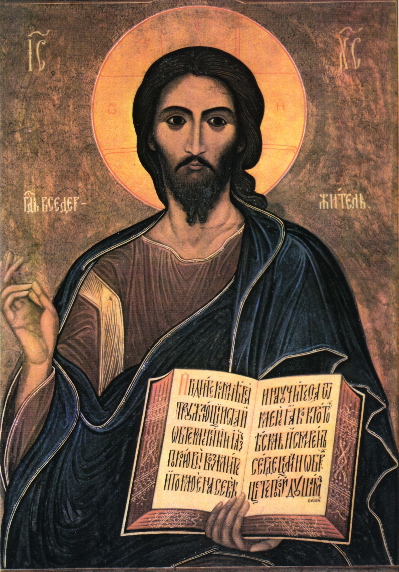

Jesus: the revelation of God

All this points to the need for constant correction and purification of our concepts of God. Christian tradition does this by focusing on the person and the life of Jesus, drawing on the experience of his contemporaries, who found in him a perfect human expression of God. Their experience has been re-affirmed by the countless millions of those since who have looked to Jesus, and committed themselves to live as his disciples. They have found him to be indeed the ‘Way’ (John 14:6): the way to connect with their deepest yearnings, and the way to connect with God. Reflection on the person, life and significance of Jesus has been for Christians the richest source for their reflections on the meaning of God, and so for their reflections on the meaning of human experience. The Catechism is a summary of what we have learned by listening to Jesus and living under the guidance of his Spirit.

We conclude this opening chapter by returning to the statement made in the Preface to the Roman Catechism (1566), quoted by the Catholic Catechism (n. 25) and referred to earlier: ‘The whole concern of doctrine and its teaching must be directed to the love that never ends. Whether something is proposed for belief, for hope or for action, the love of our Lord must always be made accessible, so that anyone can see that all the works of perfect Christian virtue spring from love and have no other objective than to arrive at love.’